May 30, 2014

I think I’ve exhausted my portfolio of adjectives. Yellowstone National Park does that to you. You can get away with it the first time, but the second time you are stricken with a galloping case of redundancy. Reflecting on our 122 mi. circuit in the northern part of YNP, I realized that the same descriptive elements came to mind even though this area was significantly different from the southern portion. So, if I repeat myself, please be forgiving.

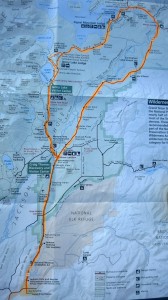

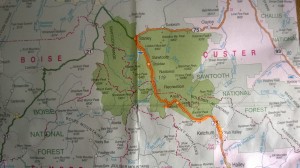

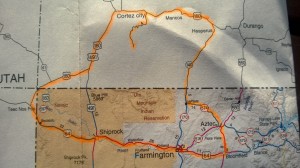

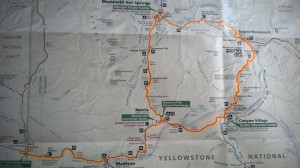

This is a map of our ride today:

We began by retracing our route east from yesterday but went north at the Norris Junction. Road work was under way and we had a 15 min. delay. We rode British style on the left as the traffic alternated one way north and south. It was a rough trip—the road was in bad shape and the bikes hopped all over the uneven surface as the contact patch of the tires was often lost. Deep but camouflaged potholes had to be sidestepped quickly. As the road climbed higher we could see Bunsen Peak (8,464 ft. elev.) and the Blacktail Deer Plateau in the distance.

Then we bounced down through two hairpin switchbacks into the valley where Mammoth Springs percolates. And, yes, it is mammoth. With an interesting hoodoo in the foreground, the springs sit on huge mound of sulfuric looking deposits.

Across from the springs, we had a picnic lunch, I re-inflated my rear tire that had lost pressure in the cold air overnight, and then we saddled up to ride east along the base of the Blacktail Deer Plateau.

The motorcycling here was exquisite. We passed tranquil alpine pastures, streams and stands of fir trees covering the hillsides. The tarmac here was fresh and smooth and our tires gripped perfectly through the twisties and sweepers that demanded attention but didn’t overwhelm.

As we swung our bikes south, we stopped at the Tower Falls for quick photos and then the fun began.

The route started its ascent near Mt. Washburn, a big boy with an elevation of 10,243 ft. The temperature dropped more than 10 degrees as we squirmed our way toward the Dunraven Pass (8,859 ft. elev.).

Banks of snow, some towering over 12 ft. , lined the east side of the road. The posted speed limit for the numerous curves never got over 25 mph. We were on the outside of the mountain; there were no guardrails and the drop off was unnerving.

Some cars and trucks like to blast their way up to the summit and get disturbing close to bikers like us who have every reason to play it safe by sticking religiously to the designated speed limit. I think it’s called survival of the smartest. We just pulled over for these hot shots and assumed that the Darwin effect would justify our cautious approach.

Cruising down from the pass we got to the Canyon Village Junction, gassed up and started our return trip along, by now, a very familiar route west since this was the fourth time we’d followed the 28 mi. stretch along the Gibbon and Madison Rivers. We knew the road well and our bikes seemed to know the way, too, happily sailing along at 45-50 mph in a sweet spot of motorcycling bliss.

The road passed through what I had begun to think of as “Bison Valley” and the scene brought to mind passages of the 23rd Psalm—phrases like green pastures, still waters, and restoration of health seemed so congruent with what we saw.

I felt incredible happiness seeing bands of noble bison plodding along, grazing and resting and caring for their young. They seemed so dignified and in complete harmony with the land and water. It’s no surprise that Native Americans honored their spirit. These shaggy but perfect animals provided food, shelter and clothing to native people and they, in turn, were grateful for the abundance these incredible creatures provided them. It would advance our culture immeasurably if we could see animals as beings more like us than different and part of the web of creation we share.

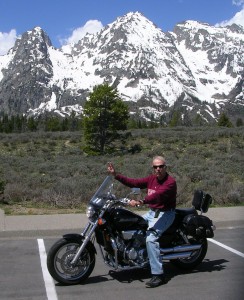

After that, we made one stop at the “rim of the caldera” where the ancient volcano collapsed after eruption and left high walls in place. There Frank took a photo of his motorcycle,”Sheba.” It was a lovely shot that Honda could use for advertising purposes.

During our caldera stop, we spied what I believed was bison poop. Frank (Paco) wasn’t sure. He scientifically inspected one of the “pies,” gave it a good sniff and pronounced it as authentically bison poop.

And so we departed Yellowstone National Park. I may never return here again, but my heart is full forever with memories of its haunting beauty.

Footnote: Thanks go to Frank “Paco” Bartlett not only for his steadfast camaraderie during all these outings but also for supplying several photos, acting as the chief science officer for bison poop, and serving as key researcher for facts and figures used in this narrative.